Remembering the crimes committed by the Saddam regime against its own people.

The consequences of the Anfal campaign , the extermination campaign of Saddam Hussein’s army against the Kurds in Iraq, have been at the center of our work in northern Iraq.

In 1988, the last year of the Iran-Iraq War, Saddam Hussein decided to resolve the problem of the Kurdish insurgents once and for all in a monstrous act of violence. In eight consecutive offensives, large parts of Iraqi Kurdistan were depopulated. First, poison gas was used against numerous villages, then the survivors were deported, some to southern Iraq, and others housed in newly built settlements along the main roads. Residence in the evacuated areas was prohibited; anyone found there could be killed without warning.

Figures for the Anfal campaign vary widely; the official estimate in Kurdistan is 180,000 people who fell victim to the massacres; around 4,000 villages and settlements were systematically destroyed, house by house. After the liberation of Saddam Hussein in 1991, most parts of northern Iraq were virtually completely destroyed, requiring repopulation. It is also important to remember that Iraqi poison gas production was carried out with the help of German companies.

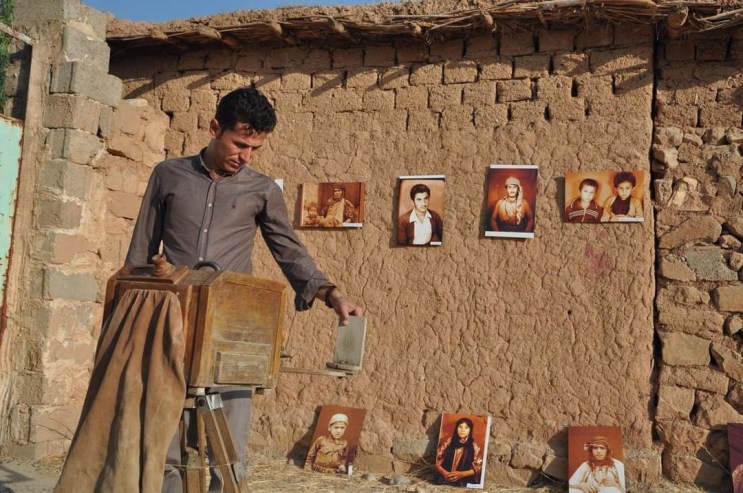

In Germian, around the village of Göptepe, which was particularly hard hit by the Anfal campaign, and neighboring communities, this resulted in a comprehensive search and documentation of the victims by teacher Hirmen Goptapi. He estimates that he has documented over 90% of the names and photographs of the victims. Around 500 residents of Göptepe alone fell victim to the Anfal campaign, just over 100 of them by poison gas, the others were deported to the southern Iraqi desert and killed there. Today, the town has a population of around 1,000.

Hirmen’s latest project is the documentation of one of the desert forts on the Saudi border, where Kurds were deported. There, one only has to scratch the ground with one’s foot to uncover bones and remnants of clothing. Hirmen plans to photographically document this site in its current state and collect memorabilia. He will travel there with one of the survivors, who was a twelve-year-old boy at the time and survived because he served the soldiers, and reconstruct the location and the processes of that time. He then plans to systematically photograph this site with four young photographers from Germian.

To truly appreciate the significance of this form of independent remembrance work, one must also consider the official commemoration, which has taken the form of large “Anfal monuments” for which a separate “Ministry of Martyrs” is responsible. Survivors and their descendants generally feel neither addressed nor represented by this form of official remembrance, which is purely focused on political representation.

https://www.facebook.com/share/v/1BeaD3ffVz/

These projects have always been accompanied by a demand that every federal government in office since then finally apologize, because without German assistance, Saddam Hussein’s regime would never have been able to produce this gas.

Then came the war in Syria and more chemical weapons attacks. Thousands were killed again, and nothing happened… except a few speeches about red lines and an agreement with the Syrian dictator that wasn’t worth the paper it was written on.

One year after the mass murder of civilians in the Syrian Ghoutas, we, together with our Syrian partner organization Al Seeraj, published a comprehensive dossier on poison gas in the Middle East , which we would like to remind you of again, because the texts and eyewitness accounts that we compiled back then, in 2014, are unfortunately still as relevant as ever.

Past, present, and future intertwine in these places; making room for the past and for remembering also means looking to the future. These usually strangely empty buzzwords of NGOs – sustainability and self-ownership are particularly popular at the moment – actually make sense here. And everything is really connected: When asked about the meaning of the slogan of Green City Halabja , the environmental program with jute bags and plastic recycling, Hero Wakel, the director of WADI’s local partner organization NWE in Halabja, first responds by referring to the poison gas attack that has made the city a symbol. “Before, we were a green city with lots of trees and gardens. And we want to make Halabja green again.” The past can quickly resurface in Halabja; the murders committed by the “Islamic State” have also shown how virulent the genocidal potential still is in the region. And so, a memorial project for Halabja, to be implemented with the support of the Hans Böckler Foundation, is not based on an abstract “commemoration” – rather, it aims to connect the past with the future. A “memory trail” – six panels are planned in the first phase – is intended to inform visitors to the city about the events of that day in March 1988 when Iraqi jets dropped those strange-smelling bombs. But the city’s development since then, its reconstruction, and the massive changes of the last 30 years will also be addressed.

All these projects aim at a programmatic connection between past, present, and future, which represents the special and ultimately successful aspect of the work in the “poison gas villages.” The projects are comparatively small, the resources employed are modest, but the work has developed continuously.

Source: https://wadi-online.de/erinnerung/

Leave a comment